after reviewing a number of sources presented at different sites, I would like to add a few more points and present my early analysis of the likely causal events for the accident (isolated on this site, without adding to the speculations winding up elsewhere. let’s wait for the official report from JTSB – and compare).

current facts as presented from official sources:

- METAR: RJTT 020900Z 33008KT 9999 FEW020 07/04 Q1016 NOSIG

- NOTAM J2253/23: [..] STOP-BAR-LGT FOR C1 THRU C14-U/S [..]

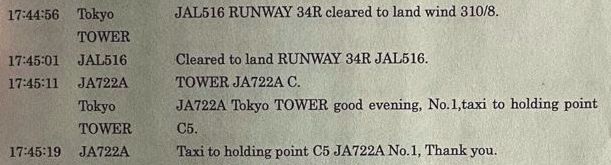

- ATC transcript (released by Japanese Ministry of Transportation)

- JAL516 had received landing clearance RWY 34R, positive readback.

- JA722A taxi to holding point C5 (34R) for #1 in sequence, positive readback.

- and additionally:

- JAL166 to continue approach as #2 in sequence, positive readback

- JAL179 to taxi to holding point C1 (34R) for #3 in sequence, positive readback

Primary question: Why did JA722A, contrary to its clearance, not hold at C5 but entered 34R ? Secondary questions of course relate to: 1) why did TWR (visually or by automated means) not identify the deviation and initiated corrective actions, 2) why was JAL516 unable to identify the abnormal condition and initiated a go-around in time.

While there is a lot to analyze on the environment and procedures related to the secondary set of questions, at this point in time, I would like to solely focus on the primary question. All assertions are speculative in nature and provided with plausible justification:

- official sources state that JA722A was a Japanese Coast Guard flight related to Jan 01 24 earthquake disaster relief. It is highly likely that in its flight plan JA722A was given status as a rescue flight and as such was given priority by coordinating stations, including Tokyo TWR.

- Consistent with (1) JA722A was cleared to hold for a (non-standard – but acceptable due to the aircraft’s lower requirement on take-off runway available) intersection (C5) take-off on RWY 34R. Tower assigned JA722A as #1 in sequence for runway 34R, relative to #2 JAL166 on approach, behind JAL516 (which has just been given already clearance to land) and to #3 JAL179 on ground for departure, cleared to taxi to (standard) holding point C1, about 30 seconds after JA722A had receive its assignment to C5. Therefore, TWR had indeed prepared a priority sequencing for JA722A, putting it ahead of competing JAL179 (which it would likely have followed to C1) and scheduling it’s departure between landing JAL516 and approaching JAL166. The effective sequence at this point in time was:

- #0 JAL516: on final, cleared to land 34R

- #1 JA722A: on ground, to hold at C5, 34R

- #2 JAL155: on approach, to continue approach 34R

- #3 JAL179: on ground, to hold at C1, 34R

- TWR in it’s communicated sequencing (starting at #1) did not further mention aircraft #0. In fact JA722A and JAL516 obviously being on the same frequency, situational awareness of the JA722A crew would have allowed them to pick up JAL516’s landing clearance right before receiving their clearance to hold at C5. Only in the case that TWR would have considered issuing a conditional “line up and wait” clearance to JA722A (such as: “JA722A line up RWY 34R and wait BEHIND landing aircraft on final BEHIND”) TWR would have mentioned the landing traffic.

- On CCTV footage from the airport camera (www.youtube.com/watch?v=6NbVdIoJsHY&t=169, Note: Please enlarge the video to full screen and monitor the faint white dot moving just above the upper edge of the tail of the distant ANA aircraft that just started taxiing from the illuminated area of the apron towards the darker runway area), at video time 3:00 one can see JA722A to enter 34R and wait in a position aligning with the runway as its landing light turns (left) towards the camera and distinctly grows brighter. From this moment on, JA722A is holding position on RWY 34R for an eternity of 48 (!) seconds – apparently waiting for a take-off clearance – before being impacted by the landing JAL516. On the video one can occasionally distinguish the JA722A strobe lights first moving and then holding with the aircraft, but its red flashing beacon is not visible on the recording.

- The captain of JA722A was reported to be the sole survivor of this aircraft and (unconfirmed) Japanese Coast Guard sources quote him as being conscious of having received a clearance to (at least) enter RWY 34R. If the captain (LH seat) was pilot flying (PF) and RH seat was pilot monitoring (PM), there is obviously a “connection” between the captain’s statement and the apparent action of the aircraft, but a huge “disconnect” with the ATC clearance (to hold at C5) which was properly read back from the aircraft. In essence, this appears to be a catastrophic disconnect between the mental models of PF and PM. In addition, there are possible physical factors contributing to the fatal actions taken by the crew:

- (1) If PM was distracted by monitoring ATC (in English language), preparing the aircraft (working the checklists) for priority departure as #1 in sequence, PM (in his RH seat, not being the captain) was likely the only one two have an unobstructed view before line-up towards the arrival end of RWY 34R to spot (in very good visual conditions, see METAR at source 1 above) landing- & strobe-lights of JAL516. PF was likely not in this visual position, and likely not advised by PM, as this would be the case in a cockpit with well established CRM.

- (2) As stated in source 2, NOTAM indicates that runway stop lights at C5 (and other intersections) were un-serviceable. With regard to the validity of the NOTAM however, additional caution has to be exercised since further provisions in the AIP Japan and possible trigger NOTAMs may be required. If stop-bar lights were indeed not operational, the crew (and specifically PF) would lack an additional clue that the mental model of having received a clearance for line-up was invalid.

- Possible causative mental factors, such as disorientation and stress within the cockpit of JA722A could be:

- (1) night operations at a major international airport, ATC in English language, a non-commercial (coast guard) crew.

- (2) a sense of urgency and stress perceived by a likely “rescue mission” flight status and an effective priority handling, being assigned #1 in sequence for RWY 34R.

- Adding to (6) but being HIGHLY SPECULATIVE in nature, I listened to ATC recordings from Tokyo TWR (remark: I have for myself ICAO English Level 6 printed in my license, but I have to admit that Haneda TWR communications in English by non-native Japanese speakers are EXTREMELY DIFFICULT to follow) on an (amateur) source www.youtube.com/watch?v=LP1xWcyKBDs&t=912s. In fact, those Internet resources usually pool together reception of several TWR frequencies – serving different parts of the airport – in a single audio stream). At the entry point marked (15:13) the recording starts with the C5 holding clearance given to JA722A (note: the documented readback from the aircraft however has not been picked-up on this specific recording – possibly due to low radio signal strength). However, at 15:24, immediately afterwards, one can hear a clearance given to another aircraft on runway 05 to “line up and wait runway zero five”. In a state of mental stress, let’s assume the following:

- (1) JA722A had initially prepared a radio setup for several possible TWR frequencies, having the one pertaining to RWY 34R selected “active” and another frequency (for RWY 05) selected “stand-by”, possibly monitoring. Depending on the radio equipment of the aircraft, it is possible to simultaneously monitor (listen only) the stand-by frequency while being able to listen & speak on the active one. If this was intentionally or accidentally selected by the crew, then

- (2) If the mental model of PF was anticipating an expedite #1 departure out of “charlie five” by a soon to follow order to line up, the audible reception of “runway zero five, line up and wait” could be “joined” into the PF’s mental model via the word “five” and his expectation on clearance to enter the runway. The consequence would match exactly the fatal actions taken by the aircraft: line up and wait.

- One could speculate that crew communication on board Japanese Coast Guard’s JA722A was obeying to a more military “chain of command” and challenging a decision of a senior party (here: PF, captain) by a junior party (here: PM) is not a strong point in Asia, as this might further be a matter in Japanese culture. This being said, there was perhaps too little room for questioning and corrective action inside the cockpit – sadly within an extensively long waiting time right in the middle of an active runway.

Abbreviations: METAR (meteorological aerodrome report), NOTAM (notice to airmen), AIP (aeronautical information publication), RWY (runway), CRM (crew resource management), ATC (air traffic control), TWR (tower), RH (right hand), LH (left hand)